Blog post

Aluminium is all around us—in automobiles, beverage cans, airplanes, and so much more. The qualities that make it highly practical for industrial applications also make it an appealing material for artists to play with. Not only is aluminium light, strong, flexible, and corrosion-resistant, but it can be molded, extruded, riveted, welded, and painted. It has a beautiful silvery finish, and can be polished to a high shine.

While artists have used different kinds of metals since ancient times, aluminium is a relative newcomer. The process for extracting it from bauxite only dates back to the 1820s, and it took another 60 years to develop an affordable way of doing so. Soon afterwards, in 1893, the first statue made of 100% aluminium went up in London. Sculptor Alfred Gilbert’s winged Anteros (the god of requited love) stands atop the Shaftesbury Memorial Fountain in Piccadilly Circus, erected to commemorate the philanthropic works of the 7th Earl of Shaftesbury.

Aluminium became abundant and accessible at around the same time the Modern art movement began to take hold. Starting in the 1930s, Alexander Calder used cut and painted aluminium sheets for his hanging kinetic sculptures, which Marcel Duchamp dubbed “mobiles.” They were light enough to move along with air currents (a concept that has since been copied over countless baby cribs).

Abstract Expressionist metal sculptor Bill Barrett began using aluminium in the 1960s—his Hari IV stands an impressive 32 feet high, welcoming students at the entrance to New Dorp High School on Staten Island, New York. The beloved landmark was meant to evoke a student sitting at a desk with a book, but the students referred to it as “The Elephant.”

Aluminium in Pop Art

Aluminium holds a great deal of cultural symbolism, and proved irresistible for Pop artists. James Rosenquist’s The F-111 (1964-1965), in oil on canvas with aluminium, consists of 59 panels and portrays a fighter-bomber along with other images of the era, from a Firestone tire to a fork in spaghetti.

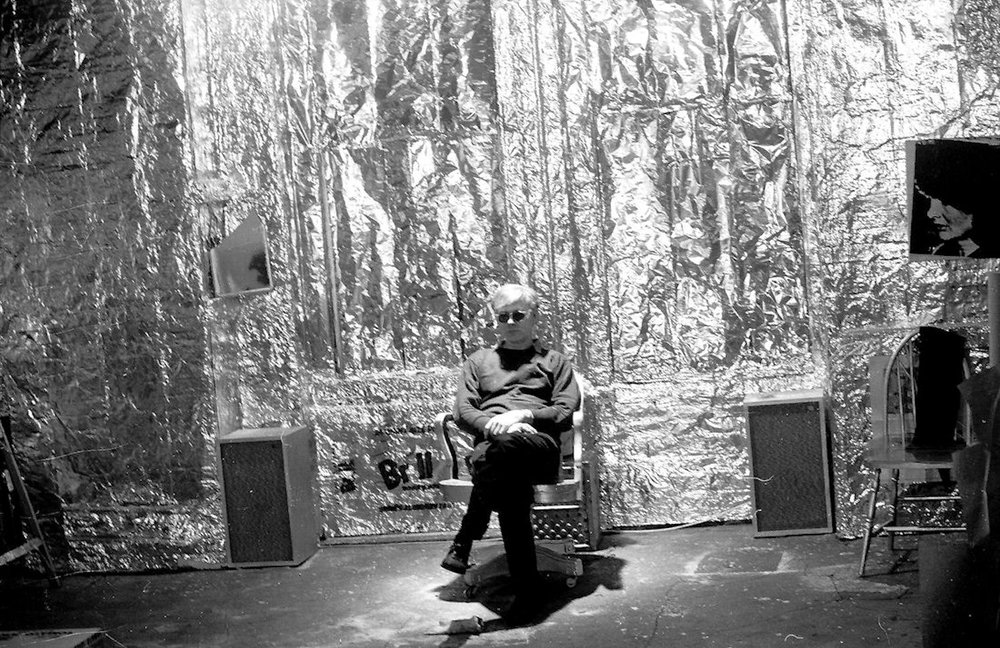

In 1966, Andy Warhol made an aluminium cast of his most iconic image, the Campbell’s Soup can (chicken with rice), covered with a silkscreened label. Warhol’s first New York studio, 1963-1967, was called the “Silver Factory” because the walls were sprayed silver and decorated with aluminium foil.

Jeff Koons spent two decades working on his monumental sculpture, Play-Doh, which resembles a 10-foot-tall mound of the soft children’s clay. In fact, the work is made of aluminium—27 interlocking pieces painted in different colors, all held together by gravity. He unveiled it in 2014 at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Recycling aluminium objects into art

Aluminium is endlessly recyclable, even into art—many sculptures and installations have been crafted from used aluminium cans and other objects. The conceptual artist Cady Noland’s Five Lane Maniac (1989) is a metal basket filled with empty beer cans. The same year, Martin Kippenberger turned an unopened beer can into part of a series called Alkoholfolter (Alcohol Torture). Richard Prince hung a stream of empty beer cans from a basketball hoop in 2008. Noah Deledda dents, creases, and crushes old aluminium cans with his thumbs until they metamorphose into surprising geometric sculptures.

El Anatsui, one of Africa’s best-known sculptors, often uses discarded aluminium caps to make sculptures that resemble tapestries. For his 2007 work Dusasa I, shown at the Venice Biennale, he flattened thousands of liquor bottle tops and stitched them together with copper wire to create a wall hanging that measures 39 feet wide and 26 feet high.

Alice Hope’s material of choice is the used can tab—she employed more than a million of them to build a site-specific installation at the Queens Museum in 2015. In her artist’s statement, she noted, “The used can tab can be looked at from a multiplicity of perspectives—that its proportion is in the Golden Mean like the Parthenon; that it’s a tool—a lever; that it’s trash; that it’s an icon; that it’s an anti-phallus with its equal negative and positive space; that as a floor plan it emulates Renaissance cathedrals with its apse and nave; its ergonomics; its timed obsolescence; its demographically democratic use, but in my work I focus on the used tab as a relic of consumption and as a token for redemption.”

From the ordinary to the sublime

The acclaimed contemporary sculptor Charles Ray works with a range of materials, playing off their weight or weightlessness, their dullness or shine, their preciousness or ubiquity. Many of his works are based on the human figure. One life-sized sculpture of a young nude woman from 2003 is painted milky white to resemble a classical marble statue, making it nearly impossible to guess the material if you didn’t know the name of the work: “Aluminum Girl.”

And in France, it took Jean-Michel Othoniel eight years to build an immersive artwork for the 12th-century Angoulême Cathedral, which he completed in 2016. The centerpiece is a monumental stained glass window made from 10,000 pieces of glass in gradations of blue, framed in aluminium latticework. It’s proof that an everyday, industrial material can also be heavenly.

Mobile from Alexander Calder

HARI IV from Bill Barrett

Andy Warhol's famous art studio, the Silver Factory

Andy Warhol's famous art studio, the Silver Factory

Jean-Michel Othoniel's immersive artwork for the 12th-century Angoulême Cathedral